A Call to Halt AI Development

Twelve days after Conversations with OpenAI’s ChatGPT went to post here, on March 22, an open letter went out from the Future of Life Institute called Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter. Its subtitle: We call on all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4.1 [emphasis added]

Open AI’s GPT-4, was released on March 14 and powers the latest available version of ChatGPT (and is set to power Microsoft’s Bing AI). It should be noted that the letter to halt development at GPT-4 includes signatures from investors of rival AI ventures, such as Elon Musk, and includes other technology figures like Apple Co-Founder Steve Wozniak.

Coming also after some public AI stumbling blocks for Google’s Bard and Bing AI, the letter expresses mounting anxiety that there are not enough protections in place for this type of AI to be in the broader marketplace. Though this type of AI is not the general intelligence AI that is often portrayed in sci-fi/horror movies, being able to sift through noise for signal and provide coherent outputs that are intelligible much of the time is remarkable. Language learning model AI’s have to be ‘trained’ using trial and error to gain proper alignment among the large pools of data that they draw upon for responses. That very database and resource intensiveness limits current AI development to mostly major players and makes the idea of a pause potentially plausible.

The Future of Life Institute’s letter was otherwise a recitation of long-held concerns of AI with a bit of epic flare [emphasis theirs]:

Contemporary AI systems are now becoming human-competitive at general tasks, and we must ask ourselves: Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? Should we automate away all the jobs, including the fulfilling ones? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us? Should we risk loss of control of our civilization? Such decisions must not be delegated to unelected tech leaders. Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable.

On April 12, the Future of Life Institute updated their open letter with a 14 page paper on policy recommendations that has 7 main points2 :

1. Mandate robust third-party auditing and certification.

2. Regulate access to computational power.

3. Establish capable AI agencies at the national level.

4. Establish liability for AI-caused harms.

5. Introduce measures to prevent and track AI model leaks.

6. Expand technical AI safety research funding.

7. Develop standards for identifying and managing AI-generated content and

recommendations.

After mentioning governing models in the United Kingdom and European Union, the paper calls for the US (and other nations) to have an agency based along the blueprint developed by Anton Korinek at the Brookings Institute. It’s primary concern would be as follows:

Monitor public developments in AI progress and define a threshold for which types of advanced AI systems fall under the regulatory oversight of the agency (i.e. systems that develop systems above a certain level of compute or that affect a particularly large group of people).

Mandate impact assessments of AI systems on various stakeholders, define reporting requirements for advanced AI companies and audit the impact on people’s rights, wellbeing, and society at large. For example, in systems used for biomedical research, auditors would be asked to evaluate the potential for these systems to create new pathogens.

Establish enforcement authority to act upon risks identified in impact assessments and to prevent abuse of AI systems.

Publish generalized lessons from the impact assessments such that consumers, workers and other AI developers know what problems to look out for. This transparency will also allow academics to study trends and propose solutions to common problems.

Beyond this blueprint, we also recommend that national agencies around the world mandate record-keeping of AI safety incidents, such as when a facial recognition system causes the arrest of an innocent person. Examples include the non-profit AI Incident Database and the forthcoming EU AI Database created under the European AI Act.

There are also requests for funding to further research and development in establishing and detecting digital provenance. This is meant to help in determining when content has been AI generated as well as passing transparency laws where consumers will have to be informed if they are interacting with an AI.

From algorithmic bias and idiocy, acting on faulty information, to affordability of large scale individualized scams and propaganda campaigns — all have been known concerns for AI development. While the Future of Life Institute’s open letter elevates the discussion of AI in the public sphere, and has some suggestions in its policy paper, it is not bringing to light a host of new concerns. Calling out GPT-4 as a benchmark seems a bit arbitrary if not suspect with signatures from rival AI developers.

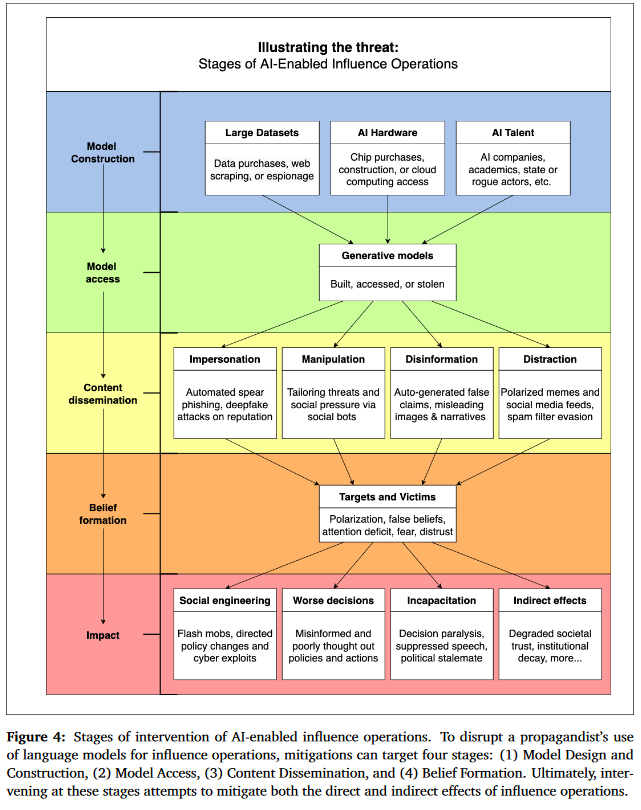

Back in January of this year, Open AI researchers, along with researchers at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology and Stanford University’s Internet Observatory, published a paper called Generative Language Models and Automated Influence Operations: Emerging Threats and Potential Mitigations.3 At 84 pages including citations, it presents an assessment of the AI landscape and some of the challenges it poses. It also has helpful charts, such as Figure 4 below that identifies best potential moments to disrupt an AI enabled influence operation.

One thing unsaid in the Future of Life Institute’s letter, is that the proposed ‘AI Pause’ would primarily impact AI development in the United States. Other entities in the world also seek to develop AI with increasing capabilities, and at some point when AI is good at training AI it could result in systems that reach incredible growth in capabilities in a short period of time. If it is truly a ‘race’ then it would seem this might be a national security risk to delay development while awaiting a different regulatory regime to emerge.

I found interacting with ChatGPT interesting, and useful as a research supplement, or as a text starter, as it appeared to thrive most in the generic and 30,000 feet overview. However, as myself and others have found, the more in-depth you go with ChatGPT (and other similarly structured AI), the more it starts to trip itself up, gets repetitive in its responses, or fixates/uses buzz-word terms with trouble elaborating such terms or ideas further. I also thought it had an issue of giving proper weight to topics in proportion to their importance when creating a synopsis or speculating based on prior written work. One comment I have seen is that it writes papers like a college “C student” — in that the paper shows that it has likely read the material and can briefly summarize major concepts — after that though… it starts to get wonky. Then again, that next step is probably a great place for a human with a higher risk tolerance to novelty or where information diverges and becomes more complicated.

In any event, it does seem that at least here in the United States, legislatures are more willing than ever to try and gain some control, or at least guard rails, on the digital landscape. An appetite that was very much on display in the two Congressional Hearings in the next sections.

C-Span and Chill - Part 1: Congressional Hearings on Twitter

On March 9, the House Judiciary Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government held a hearing that featured journalist Matt Taibbi and author Michael Shellenberger.

In the last Twitter related Congressional hearing posted here, it did seem like the conversation hinged mostly on the document collection produced in the “Twitter Files,” but which none of the people testifying were involved in its collection and publication. This resulted in a lot of questions that went nowhere along the lines of “Do you remember an email from years ago to that account you don’t have access anymore?” The Twitter Files are a series of tweets from Taibbi showcasing internal Twitter documents that he had gained access to after being contacted directly from someone he refers to as “Sources at Twitter.” Public record, including Taibbi’s own Substack, suggests that “Sources at Twitter” is current Twitter owner Elon Musk. Even in the hearing when pressed on the nature of association or relationship with Musk by House Representatives, Taibbi would not answer and invoke protection of his journalistic sources.

Stacey Plaskett (delegate from the U.S. Virgin Islands) was able to get information that could help establish the document universe question I had posed regarding the digital collection that Taibbi and Shellenberger had exposure:

Plaskett: “Probably millions of emails and documents, right, that’s correct?”

Both: “No - Less - Sounds too high.”

Plaskett: “Ok, a hundred thousand?”

Both: “Probably - yeah.”

Shellenberger also stated they “never had a request denied.”

At the date of the March 9 hearing, the tweeted Twitter Files included 338 internal documents, or approximately 0.338% of the document universe accessible to Taibbi and Shellenberger according to their testimony.

We also learned more about Taibbi’s method of determination for including documents in the Twitter Files:

Plaskett: “So what we’re getting is your dissemination, your decision as to what was important or not important, correct?”

Taibbi: “-which is true in every news story.”

Ok. So, one legal thing about the Twitter hearings from a First Amendment standpoint is that there appears to be no dispute among the Committee that Twitter can control/moderate its own system. There also appears to be no real dispute that Twitter may ask government agencies for input in making moderation decisions and policy, or in being made aware by government agencies and independent contractors that accounts may be violating the law or Twitter’s terms of service.

For Taibbi though (and presumably Shellenberger), that there is any contact at all are apparently examples of an assault on the First Amendment of the US Constitution. However, from what Taibbi says, and he sounds like a lot of non-attorney people to be fair, in that the First Amendment merges into a personal, or novel legal conception. In this case the conception is that the First Amendment equates with an unrestricted freedom of individual expression anywhere, at all times, and regardless of existing laws, ownership, or content.

This kind of broad conception is not legal reality. For example, speech like fraud has been traditionally criminalized in the United States. Fraud is codified in all states of the union. I know ‘people’ on the internet might say lying is free speech, but the legally correct answer in the United States of America is that it depends on what you are lying about, to whom-when-where you lie, and if there are damages ($) as a result of your lying. My estimation is that the vast majority of people in the United States do not want the First Amendment to excuse fraud. I think this is understandably so, because at its inception the First Amendment is supposed to help arrive at truth via deliberation. First Amendment jurisprudence is a spectrum that prioritizes legitimate political speech — meaning you can criticize the government to your heart’s content (with errors), but cannot coordinate an imminent overthrow of the government — on one end — and then in the middle-ish there is commercial/advertising speech (punishing bullshit claims and scams like an off-the-shelf flashlight cures cancer) — and then on the other end is fraudulent/criminal speech (such as true threats, harassment, and the like).

The First Amendment restrains government action, and that has been historically more than emails from an agency finding posts on a website and asking if they violate a website’s terms of service. Also, in Twitter’s case, during the discussed time period that saw huge spikes around the world submitting legal requests, its compliance rate is about 40% for information requests and 50% for takedown demands. The last available Twitter transparency reports are a couple years old as Musk’s takeover appears to have also ended Twitter’s biannual transparency reporting. This undercuts the argument that Twitter was being held hostage, and largely why I think the references to First Amendment infringements made by Taibbi are incorrect from a Constitutional Law perspective.4

Apart from the shaky legal analysis, I also have doubts regarding the investigative competency of the few people Musk tapped for the Twitter Files. While I do not doubt the writing ability of Taibbi or Shellenberger, I am not aware of them ever doing this type of investigation. I have worked on million-plus document investigations and their described process for the hundred thousand document universe provided to them sounds a bit slap-dash — though this seems partly due to them being pressed for time — one assumes by Musk. The search terms they used to find the 338 documents have also not been shared publicly as far as I am aware.

Just from a numbers perspective, there were roughly 7,500 Twitter employees prior to Musk laying-off nearly half of them. All the public gets to see are 338 documents from a document universe of 100,000 of an unknown date range?

Eh. By all means, criticize Twitter if it has been hypocritical. However, these releases are not something I would give a ton of credence for hard claims on government censorship run amok that violates the First Amendment or the weaponization of the federal government. Especially when a lot of the released emails show Twitter capable of pushing back/saying no to requests from state and non-state entities. When Taibbi was asked in an interview on MSNBC if he looked for information about censorious requests from then-President Trump, Taibbi demurred on the topic “because I didn't have that story.”

Recently, Substack announced Notes, which is a way to blurb about your posts on Substack similar to Twitter. This caused a stir with “Sources at Twitter”/Elon Musk. Musk even tweeted out part of an instant message conversation between himself and Taibbi regarding this matter, which has Musk mistakenly thinking of Taibbi as an employee of Substack (granted Taibbi and Substack appear to have a cozy relationship given that Taibbi has posted screenshots texting directly to Substack’s co-founder). Ironically, after Musk thought Taibbi insufficiently loyal to Twitter’s interests, Taibbi’s account was itself shadowbanned by Twitter, which also included the Twitter Files. Taibbi has since left Twitter and taken up posting at Donald Trump’s Truth Social.

To summarize: After a few journalists are tapped by Musk, they attempt to navigate approximately 100,000 documents provided to them in a short amount of time (meaning days not weeks). They cannot put eyes on all of those documents so they use search terms that they felt were pertinent to a story they wanted to tell. They eventually publish 338 documents according to conditions set by “Sources at Twitter” aka Elon Musk. The main condition was that everything had to be published exclusively on Twitter.

Since purchasing Twitter, Musk has strayed from his free speech pretenses in practice. From the Adam Serwer at the Atlantic:

During his tenure at Twitter, Musk has suspended reporters and left-wing accounts that drew his ire, retaliated against media organizations perceived as liberal, ordered engineers to boost his tweets after he was humiliated when a tweet from President Joe Biden about the Super Bowl did better than his own, secretly promoted a list of accounts of his choice, and turned the company’s verification process into a subscription service that promises increased visibility to Musk sycophants and users desperate enough to pay for engagement. At the request of the right-wing government in India, the social network has blocked particular tweets and accounts belonging to that government’s critics, a more straightforward example of traditional state censorship. But despite all of that, he has yet to face state legislation alleging that what he does with the website he owns is unconstitutional.

I wonder to what extent that Musk as CEO perceived Taibbi and company as good marks from the outset. At the time, Taibbi would be near the top of a list of contrarian independent media professionals (along with indy media maven Bari Weiss and buddy Michael Shellenberger). However, the subsequent investigation’s artificially imposed time crunch, restricted publishing process, and secretive attitude is all a bit strange to me compared to an average internal investigation or reporting.

Taibbi and Shellenberger are welcome to their First Amendment interpretations that don’t match up to the law. Musk can obviously do what a new owner of a social media company is want to do in the current legal landscape. I’ll stick to Substack Notes.

At the end of the day, most issues raised still seem to come down to peoples displeasure with algorithms that mindlessly categorize people and their posts — at times incorrectly (at least arguably so) — and related disagreements with the people tasked with refereeing a website using those algorithms. However, that is a different post, and probably its own Congressional hearing.

C-Span and Chill - Part 2: Congressional Hearings on TikTok

TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew testified in front of the House Energy and Commerce Committee on March 23. TikTok has recently come under fire from bills crafted to ban it outright in the USA because TikTok is owned by ByteDance, which is based in China, and subject to the CCP’s rules letting the CCP do as it pleases without regard to legal form. This has caused concerns regarding the app’s security. This is not entirely unjustified with regards to user metadata, but there was nothing presented at the hearing that the CCP was directing TikTok to drive or promote specific content (even though it seemed some House Reps believed this to be the case).

The nearly five hour hearing covered, and then re-covered, mostly familiar social media gripes. House Representatives were at times confused about whether Singapore was its own country, and I felt bad for Shou Zi Chew (who is from Singapore, which is not in China), and wondered about issuing an apology to the country of Singapore on behalf of Americans because it seemed like our Representatives are unaware that it is its own nation.

Anyhow, even though it was longer than the Twitter hearing above I have less to say about it because the hearing was a bipartisan effort to put TikTok on BLAST. The committee looked at other areas where they felt TikTok was detrimental to the United States, such as young people spending too much time on the app or the content being too low-brow. TikTok’s CEO seemed a bit bewildered by the accusations and informed the committee that extensive parental controls exist and TikTok’s policies practices are not unique for a social media company. In an effort to allay data concerns, Chew also promoted Project Texas where TikTok would keep all of its US data on servers located in the United States.

No one seemed to be going for that, and though TikTok’s sins as a social media company are not unique, the Representatives seemed to want to converge upon Chew like a pack and rend him apart — in a bipartisan manner.

Poem for 2023.04.17

Light shines in evening

Metal beak breaks through hard soil

Bulbs lay in close rows

Out-And-About Photo(s) for 2023.04.17

These birdhouses go up in the nearby apple orchard occasionally.

From last week:

From late February:

Future of Life Institute: Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

Future of Life Institute: Policy Making in the Pause https://futureoflife.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/FLI_Policymaking_In_The_Pause.pdf

Generative Language Models and Automated Influence Operations: Emerging Threats and Potential Mitigations https://arxiv.org/pdf/2301.04246.pdf

If interested in conceptualizing things like the First Amendment for companies like Twitter, check out the [G]Press post, Twitter is a Button Factory.